Power dynamics

How to exercise influence without formal authority?

Neu-Ulm University of Applied Sciences

February 14, 2024

Introduction

Managers have to understand and develop new sources of power and influence if they are going to be able to defend their groups’ interests. Thus, they must become “political”— i.e., understand the political dynamics of organizations and build the power and influence necessary to navigate them. Hill (2003, p. 272)

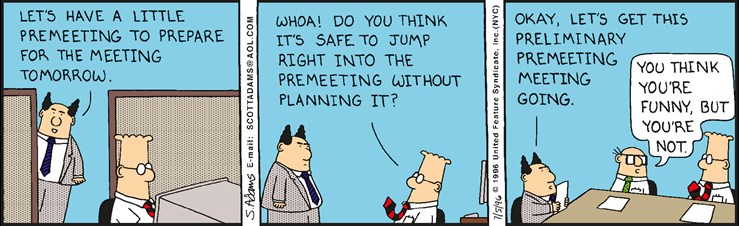

Preparing for politics …

Dicussion

Does leadership require the art of politics?

If so, what do you associate with it?

On power and politics

Many new managers erroneously believe that the “powerful” are those in more senior positions, because they equate power simply with formal authority Hill (2003, p. 272)

Power in organizations

Organizations can be seen as both, cooperative systems of employees working together to achieve goals and political arenas of individuals and groups with differing interests (Brass, 2017).

Power can be defined as the ability to get other people to do what you want them to do, politics as power in action, using a range of techniques and tactics (Buchanan & Badham, 2020).

Power and politics is at the heart of how organizations function (Hill, 2003).

Though, often associated with negative connotations, Buchanan & Badham (2020) shows that the view of the damaging, negative consequences of politics is too narrow. Politics can be both ‘functional’ and ‘dysfunctional’.

Power and leadership

Other things being equal, political conflict increases with growing interdependence, diversity, and resource scarcity (Pfeffer, 1992).

Managers who ignore or fail to understand how power and influence work in organizations will find that they and their teams experience difficulty in being effective and ethical in their work. Hill (2003, p. 273)

Development of competing coalitions and periods of organizational crisis exacerbate political conflict, while leadership and shared value help to reduce the amount of conflict (Hill, 2003).

Leaders need to define a vision that aligns and motivates people, creates shared values, and a shared culture—these are critical mechanisms for managing the increased diversity and interpedendence in organizations today.

Political conflict in organizations

Sources of power

Discovering that formal authority is a very limited source of power, new managers must find other ways to get things done […] they soon learn that power and influence are the meachnisms by which the inevitable political conflicts in organizations get resolved. Hill (2003, p. 274)

Dicussion

If it is not a formal authority, what are the main sources of power?

Personal and positional characteristics

Sources of personal power (Hill, 2003, p. 276)

- Expertise: relevant knowledge and skills

- Track record: relevant experience

- Attractiveness: attributes that others find appealing and identify with

- Effort: expenditure of time and energy

Sources of positional power (Hill, 2003, p. 276)

- Formal authority: position in hierarchy and prescribed responsibilities

- Relevance: relationship between task and organizational objectives

- Centrality: position in key networks

- Autonomy: amount of discretion in a position

- Visibility: degree to which performance can be seen by others

Discussion

Why is a strong, well-developed network a meaningful source of power?

Relate your answers to the social capital theory.

Building key relationships

Companies are increasingly required to engage in cross-organizational work (across levels, functions, geographies) in an effort to improve their capacities to execute and innovate.

Leaders need to build and maintain key relationships to identify changes in the priorities and needs of these groups and prepare their field for new opportunities and threats—a strong, well-developed network can provide the kind of big picture information needed in today’s world (Brass & Krackhardt, 2012).

It is, thus, required to identify dependencies1, to take into account the political dynamics that make for potential sources of conflict2, and to invest time and energy in building and maintaining relationships with those on whom the team is dependent3 (Hill, 2003).

It is always better to overestimate rather than underestimate dependencies. Hill (2003)

In brief

It is not what you know,

it is who you know.

- Gaining membership to exclusive clubs requires inside contacts

- Attractive jobs are usually won by those with friends in high places

- Friends and family constitute the final safety net if one falls hard

The core intuition guiding social capital research is that the goodwill that others have toward us is a valuable resource Adler & Kwon (2002)

Definitions

Social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity, but a variety of different entities having two characteristics in common: They all consist of some aspect of social structure, and they facilitate certain actions of individuals who are within the structure. Like other forms of capital, social capital is productive, making possible the achievement of certain ends that would not be attainable in its absence Coleman (1988, p. 98)

… features of social organizations such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefits Putnam (1993, p. 67)

… the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition Bourdieu (1986, p. 21)

… the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or an social unit. Social capital thus comprises both the network and the assets that may be mobilized through that network. Nahapiet & Ghoshal (1998, p. 243)

Similarities and distinctions

The definitions of social capital share some similarities and distinctions:

- There is an emphasis on the structure of social relations (networks)

- Social capital is seen as a resource for action (individual goal achievement)

- The level of analysis stems from macro-level to meso/micro-level

- The causal structure of social capital is conceived differently

- Networks as source of social capital; social capital is a result of network embeddedness (e.g., Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988).

- The network of relations is equivalent to social capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; e.g., Putnam, 1993).

Strong vs. weak ties

Coleman (1988) argues that cohesion, that is to say the strength of the relationship between actors, is the source of social capital (strong ties)

- Cohesion facilitates the creation of social norms, trust and sanctions within networks, which safeguard against opportunistic behavior

- Cohesion enables coordination and increases willingness of actors to engage in knowledge exchange (bonding)

Burt (2018) posits that social capital rather emerges from opportunities to bridge disconnections or non-equivalencies separating non-redundant sources of information (structural holes)

- Structural holes (i.e. ‘weak ties’) provide the opportunity to get access to diverse sets of perspectives, skills, or resources.

- Social capital emerges from structurally favorable positions between different group of actors (bridging)

Structure, cognition, and relation

Value

The ultimate value of a given form of social capital is context-dependent (Adler & Kwon, 2002).

Strong ties

Effective search for novel information

(competitive rivalry, certain tasks, individual contribution)

Weak ties

Effective transfer of information and tacit knowledge

(collective goals, uncertain tasks, group contribution)

The value is further dependent on the availability of complementary resources (e.g., combination capability)

Opportunity, motivation, and ability

Final remark

It is not what you say, but what you do. Truism

Q&A

Literature

Footnotes

Dependencies can be analyzed by asking questions such as On whom am I dependent, and who depends on me?

Political dynamics can be understood by asking, e.g., What differences exist between me and the people on whom I am dependent? What sources of power do I have to influence this relationship?

Questions like What can be done to cultivate or repair the relationship? help to cultivate relationships

Social capital theory