Foundations

What is leadership and how should leaders think?

Neu-Ulm University of Applied Sciences

February 14, 2026

Learning objectives

After completing this unit, you will be able to:

- Distinguish leadership from management and explain why the digital age demands distinct leadership capabilities.

- Explain what mental models are and why a latticework of models improves decision-making under complexity.

- Apply core generic, systems thinking, and human behavior mental models to leadership scenarios.

- Evaluate the limitations of any single mental model using the “map vs. territory” principle.

Introduction

Digital leaders empower people with vision, understanding, clarity and agility. Waltraud Glaeser, Leadership Coach

Definitions

Progression

From leadership to the digital age to digital leadership.

Discussion

What is leadership?

Leadership defined

A leader … is like a shepherd. He stays behind the flock, letting the most nimble go out ahead, whereupon the others follow, not realizing that all along they are being directed from behind. Nelson Mandela

Leadership

Winston & Patterson (2006, p. 8) define leadership as:

One or more people who selects, equips, trains, and influences one or more follower(s) who have diverse gifts, abilities, and skills and focuses the follower(s) to the organization’s mission and objectives causing the follower(s) to willingly and enthusiastically expend spiritual, emotional, and physical energy in a concerted coordinated effort to achieve the organizational mission and objectives.

Management

Kotter (2017) differentiates leadership from management as follows:

Management is about coping with complexity,

while leadership is about coping with change

Discussion

Why speak about

digital leadership?

What is specific about the digital age?

Context of leadership

The digital age is coined by digital technologies (e.g., Social media, Mobile computing, Analytics/big data, Cloud computing — SMAC) that are inherently disruptive and that cause major changes (Karimi & Walter, 2015).

Verhoef et al. (2021) identifies three phases of these disruptive changes:

digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation.

- Digitization is the “the process of converting analog signals into a digital form, and ultimately into binary digits (bits)” (Tilson et al., 2010, p. 749).

- Digitalization is “a sociotechnical process of applying digitizing techniques to broader social and institutional contexts” (Tilson et al., 2010, p. 749).

- Digital transformation is “a process that aims to improve an entity by triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies” (Vial, 2019, p. 118).

Discussion

What are specifics of the digital age that require distinct leadership skills?

Disruptive potential

Digital technologies do not develop linearly, but exponentially, which is leading to significant changes in people’s behavior, attitudes, and expectations.

Acceleration of VUCA

Volatility

Uncertainty

Complexity

& Ambiguity

Digital leadership

Digital technology has changed and is changing organizations’ structure, work environment, processes and culture, in an irreversible way, creating new challenges that leaders have to face.

Organizational leaders must work to ensure that their organization is capable of responding to the disruptions associated with the use of digital technologies and of responding to the changes (Vial, 2019), e.g., by

- dissolving inertia and resistance to change,

- leading employees to assume roles that were traditionally outside of their functions,

- acting as boundary spanners that foster close collaboration between business and IT functions,

- depending on analytical skills to solve increasingly complex business problems,

- ensuring that digital technologies are properly leveraged (i.e., used).

Digital leaders empower people with VUCA — vision, understanding, clarity and agility.

Mental models

Opening quote

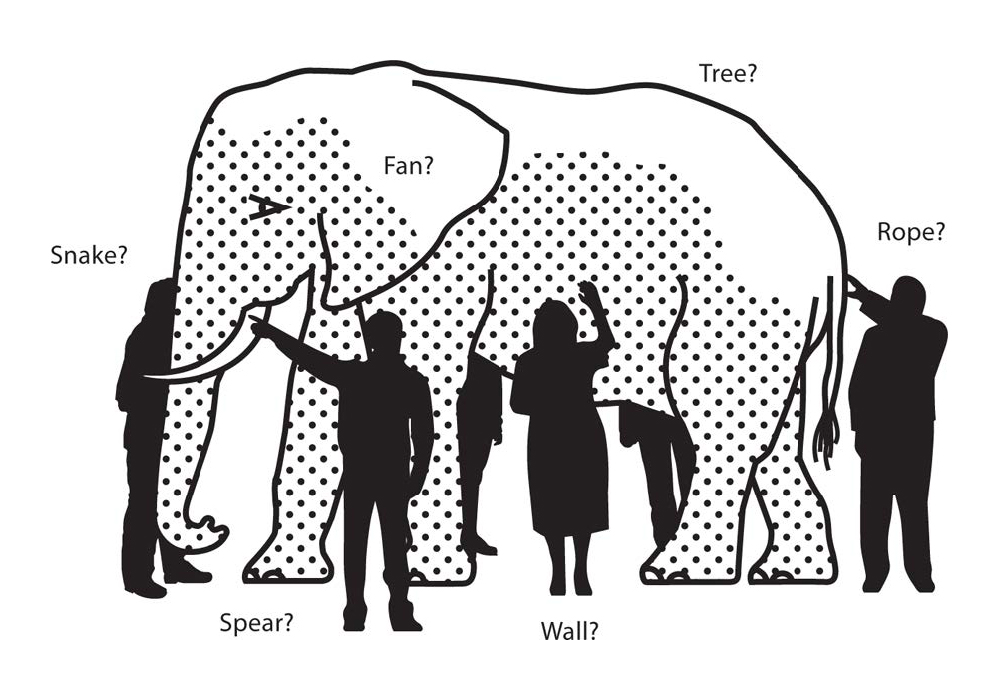

In life and business, the person with the fewest blind spots wins. Shane Parrish

The decision-making crisis

Leadership is challenged with information overload (2.5 quintillion bytes created daily), increasing complexity of systems, and a VUCA environment (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous).

Paradox

We’re trained to become specialists, yet specialization itself creates blind spots. Parrish (2020)

Technical expertise alone is insufficient for effective digital leadership.

This is why we need mental models from multiple disciplines

— they help us see beyond our specialization.

The problem with specialization

Latticework thinking

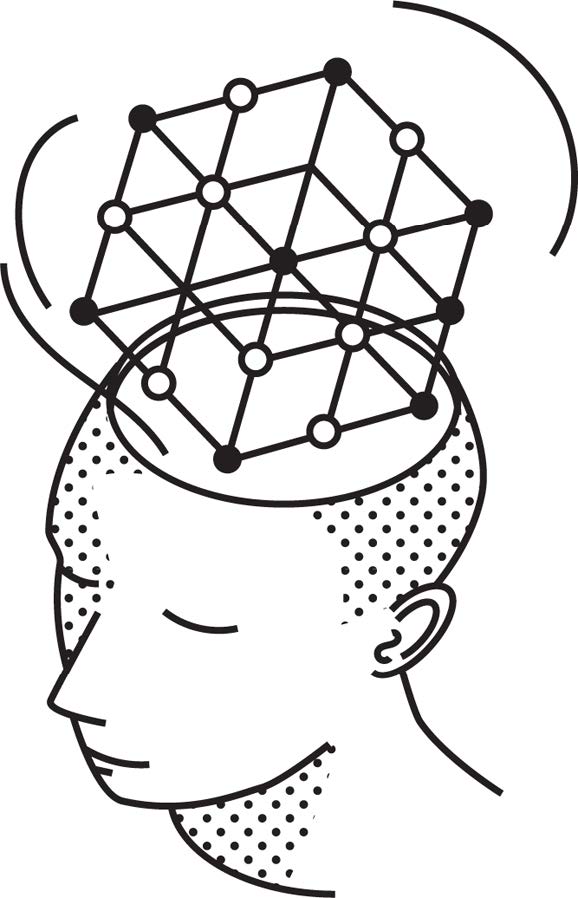

Mental models

Johnson-Laird (1983) shows that humans don’t naturally think using the rules of formal logic (like syllogisms or propositional calculus). Instead, we construct simplified mental representations or “models” of situations and mentally simulate what might happen within those scenarios.

A mental model is a cognitive representation such as a conceptual framework or worldview that helps us understand and interpret the world (Jones et al., 2011).

Discussion

Have you ever seen something fail because people were looking at a problem in a narrow way?

The latticework approach

Worldly wisdom requires models from all important disciplines (Parrish, 2020).

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models. Charlie Munger, Partner at Berkshire Hathaway (1924-2023)

(Parrish, 2020, p. 22)

Mental models x leaders

Introduction

Mental models provide the understanding of how a system works and allow us to use heuristics to quickly navigate within that system.

Mental models are the key to making heuristics fast, frugal and accurate strategies. Such simple mental shortcuts in turn, enable rather than restrict decision-making under uncertainty (Gigerenzer et al., 2022).

Generic mental models

Generic mental models are models that are broadly applicable across multiple domains, disciplines, and situations, rather than being specific to a single field or context.

According to Parrish (2020) some effective generic mental models are

first principles thinking, second-order thinking, probabilistic reasoning, inversion, and Occam’s razor.

Systems thinking models

Systems thinking models are mental frameworks that help us understand complex systems by focusing on relationships, interactions, and emergent properties rather than isolated components.

Important system thinking mental models are

complex adaptive systems, feedback loops, emergence, and network effects.

Human behavior models

Human behavior models are conceptual frameworks that help explain, predict, and influence how people think, decide, and act. These models are particularly valuable for digital leaders who need to understand both individual psychology and group dynamics when designing systems, implementing change, or leading organizations.

Human behavior models include

incentives, cognitive bias, social and group behavior models, and learning curves.

Implications

Map vs. territory

The map is not the territory … the only usefulness of a map depends on similarity of structure between the empirical world and the map.3 (Korzybski, 1958).

As all models are wrong, but some are useful:

- Continually test and update models

- Maintain epistemic humility

- Seek disconfirming evidence

- Use multiple maps of the same territory

Build your latticework

Start with fundamental, versatile models, build deliberately across disciplines, and test models through application.

Three-step approach:

- Learn (study diverse fields)

- Apply (use models in real decisions)

- Reflect (record outcomes and refine)

Latticework x this course

Building your latticework — unit by unit

Throughout this course, each unit adds new mental models to your latticework. By the end, you will have built your own leadership latticework — a diverse, interconnected set of thinking tools you can apply to real leadership challenges.

The latticework grows with every unit:

- Unit 1 — First principles, inversion, second-order thinking, systems thinking, map vs. territory

- Units 2–8 — Each unit introduces domain-specific models (traits, paradoxes, motivation, teams, power, stakeholders, culture)

- Unit 9 — Storytelling as the meta-model for communicating your latticework to others

Your latticework canvas

Use this template to track your growing latticework throughout the course:

| Unit | Mental models added | How I applied them |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Foundations | ||

| 2. You, the leader | ||

| 3. Adaptive behavior | ||

| 4. Environments | ||

| 5. Team | ||

| 6. Conflict & Power | ||

| 7. Stakeholder | ||

| 8. Context | ||

| 9. Communication |

Transition

Mental models help us think — but who are we as thinkers and leaders?

Next, we look inward at leader characteristics: What traits shape leadership? Where do they come from? And how can self-awareness become a foundation for effective leadership?

Homework

Read Judge et al. (2002) and answer following questions:

- What are the most salient aspects of personality as proposed by the five-factor model of personality (i.e., Big Five traits)?

- How are these traits found to relate to leadership?

- What surprised you most?

Q&A

Literature

Footnotes

Moore’s law is the observation that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years

Metcalfe’s law states that the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system

Korzybski developed this concept during a period when many fields were grappling with the limits of human understanding - similar to our current AI era.