Process

Some thoughts on structuring research projects

Neu-Ulm University of Applied Sciences

Research process

Recap

Form small groups, have a look at your notes on Hund et al. (2021) and synthesize your answers to the following questions:

- How do the authors theorize?

- What is their theoretical contribution to the existing body of knowledge?

- What are the building blocks of their theory?

Product and process

Science is both a product (the body of knowledge) and a process (doing scientific research).

- It is exciting—discovery of new

- It is ongoing—never finished

Science is ongoing

All scientific knowledge is a set of time-bound conjectures.

The body of knowledge—the product of science—describes the current accumulation of what we know, what we can measure, what we claim to explain (e.g., theory, evidence, methods).

- It is at the heart of science—starting point and object.

- It is available in the scientific community in the form of paper, articles and books.

- It is constantly evolving—it moves and grows every day.

Generic process

Role of literature

On giants

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants. Sir Isaac Newton, English scientist (1642 -1726)

Read before you write

Types of knowledge

You need to acquire at least three types of knowledge before yo can even start your research (Recker, 2021)—knowledge about:

the domain and topic, relevant theories and available evidence & relevant research methods

Read-interpret-write

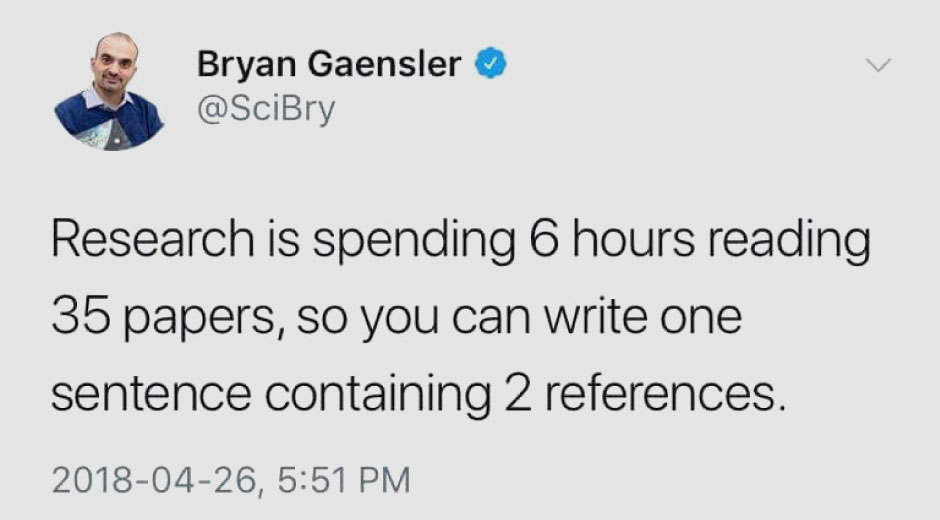

When consuming scientific literature, it’s not always necessary or efficient to read every sentence from start to finish.

You can apply the read-interpret-write strategy to keep focused and make the most of your reading (adapted from read-think-interpret strategy in Recker, 2021).

- Read — before diving into the details, skim the title, abstract, introduction, headings, subheadings, and conclusion; then identify key sections that contribute to your objectives and read those piece by piece

- Interpret — think about the piece’s relevance for your research and evaluate whether there are useful ideas, theories, concept, methods, or findings you should investigate in more depth

- Write — Keep a (digital) notebook where you note down key takeaways, questions, and reflections.

While reading, interpreting and writing, always keep your research goals in mind.

Where to find literature

Build on the shoulder of giants—your research should build upon high quality readings, which are usually found in leading journals and conferences (especially recent topics).

- Journal and Conference Rankings for Information Systems/Management

VHB JourQual 3, AIS Senior Scholars’ List of Premier Journals, or ABS Academic Journal Quality Guide - Also look in related fields (e.g., in management or psychology), particularly for theory literature

E.g., scan recent publications in the journal/conferences of the Academy of Management (AOM)

Initially, scan leading journal/conference; start with the most recent articles.

Later, adopt a structured approach, e.g., run structured queries against databases such as the the AIS eLibrary or Web of Science.

Forward and background search

Look beyond a read to avoid overlooking relevant parts of the literature.

- Backward search—look at the references of the paper you are reading in order to uncover important/seminal articles.

- Forward search—use a database (e.g., Google Scholar) to identify articles citing the paper you are currently reading. This helps to uncover more recent articles that build upon the topic you are engaging with.

Exercise

Do an exploratory search for literature on a phenomenon that interests you.

- Identify 3-5 papers that might help you to acquire relevant cumulative knowledge

- Try to skim the papers and assess their relevance (i.e., does it reveal a theoretical or methodological perspective that would be useful?)

- Evaluate the dependability of these papers (i.e., in how far are these giants?)

Summaries

You might not be the first, so look for and utilize structured literature reviews:

They contribute to the overall understanding of a subject area and highlight areas for your research.

Exercise

Search for a structured literature review on your topic, a particularity of it, a theory that could inform your study, or a method you could use.

Additional resources

The information systems discipline also has excellent web resources that are dedicated to the literature about theories and methodologies:

Systematic literature review

A systematic, explicit, and reproducible method for identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing the existing body of completed and recorded work produced by researchers, scholars, and practitioners. Fink (2019, p. 17)

Types of literature reviews

There are three different types of literature reviews (Okoli, 2015):

- Review for the background section of a paper that gives the theoretical foundations and context of a research question and helps to bring the question into focus

- Review for a graduate thesis (”thesis literature review”)

- Standalone literature review that is a journal-length paper that reviews the literature in a field without the author’s collecting or analyzing any primary data (“systematic literature review”, SLR)

The focus here is on the last one, which is distinguished by its scope and rigor.

Purpose

A systematic literature review is usually conducted to

- analyze the progress of a specific research stream,

- make recommendations for future research,

- review the application of one theoretical model in the IS literature,

- review the application of one methodological approach in the IS literature,

- to develop a model or framework, or

- to answer a specific research question that is not related to the above goals

Process

Searching for literature

It is most efficient to use open access databases (such as Google Scholar and the Directory of Open Access Journals) and specific subject databases (such as ProQuest, Scopus, EBSCO, IEEE Xplore and the ACM Digital Library) to search for literature.

Search queries that reflect the defined search and inclusion criteria need to be defined.

The search should be supplemented further by backward and forward search.

Research questions

I believe that the choice of research problem –choosing the phenomena we wish to explain or predict –is the most important decision we make as a researcher. We can learn research method. Albeit with greater difficulty, we can also learn theory-building skills. With some tutoring and experience, we can also learn to carve out large numbers of problems that we might research. Unfortunately, teasing out deep, substantive research problems is another matter. It remains a dark art. Ron Weber, former EIC MIS Quarterly (2003)

We will discuss some strategies on topic choice in the Academic Writing course.

What is it?

The research question is a logical conclusion to a set of arguments.

These arguments stress that there is

- an important problem domain with

- an important phenomenon that deserves attention and that relates to

- an important problem with the available knowledge about this type of phenomenon.

Example

- Organizations invest heavily in new IT, seeking benefits from these investments.

- Many of these benefits never materialize because employees do not use the technologies.

- The literature to date has only studied why individuals accept new technologies but not explicitly why individuals reject technologies. This is a problem (Cenfetelli & Schwarz, 2011).

- Therefore:

Why do people reject new technologies?

Motivating a research questions

Gap vs. hook.

The gap is usually the argument that something hasn’t been done yet.

The hook is a strategy to find a problem that someone cares about.

A bad gap is “nobody has studied …”, a good gap indicates a problem.

Specification

Research questions are typically one of two types (Recker, 2021):

Type 1:

What, who, and where?

Type 2:

How and why?

Quality-checks

The research question help you focus the study and give you guidance for how to conduct it.

Recker (2021) proposes following principles to reflect on if a RQ serves these functions well.

- Short: Research questions have to be concise (rule of thumb: one line of text, max. 1.5 lines).

- Feasible: You should have answers to at least following questions: Are you able to observe all concepts you use in the research question? Are adequate subjects of study available? How will you collect the data? How will you analyze the data? Do you have the technical expertise, the time and money?

- Interesting: You are confident that you can maintain an interest in the topic and maintain your own motivation to study it.

- Novel: An answer will confirm or refute previous findings or provide new findings.

- Ethical: Pursuing and answering the question will not violate ethical principles for the conduct of research, and will not put the safety of the investigators or subjects at risk.

- Relevant: Both the question and the future answer(s) are important in the sense that they inform scientific knowledge, industry practice, and future research directions.

Exercise

Analyze the research questions of the papers identified (either in a small group or individually).

Apply the quality-checks outlined above.

Formulate 1-3 own research questions.

Homework

Read the literature review you have found on a topic that interests you and make notes on following questions:

- What are relevant concepts?

- What theories have been applied to study the phenomenon?

- What methods have been applied to build, test, or expand the theories?

- What would be justified RQs to that topic?