Opening remarks

Overview

Qualitative research aims to understand phenomena within the complexity of real-life contexts through direct observation, communication with participants, or analysis of texts, and may stress contextual subjective accuracy over generality (Recker, 2021).

Qualitative methods are helpful

- when the boundaries between phenomena and context are not transparent

- when a phenomenon is not yet fully understood, not well researched, or still emerging

- for studying social, cultural, or political aspects of a phenomenon

The methods focus on the “why” and “how” of things rather than the “what,” “where” and “when” of things and involve detailed study of a small sample or group. They are, thus, often used for theory building.

Popular quantitative research methods

- Case study

- Action research

- Ethnography

- Grounded theory

Basic principles

Following basic principles are common to qualitative methods (Recker, 2021):

- Natural setting: studying a phenomenon in the context in which it occurs

- Holistic and contextual: developing a comprehensive, detailed picture of complex phenomena

- Researchers as a key instrument: researchers collect data and information themselves

(rather than through an ‘objective’ instrument) - Multiple sources of data: e.g., interviews, documents, observations

- Evolutionary design: the research process is evolutionary in nature

- Inductive analysis: bottom-up analysis of data, focus on emergent meaning

(often following an interpretative approach)

Differences to quantitative research

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | to explain & predict; to test, confirm and validate theory | to describe & explain; to explore, interpret and generate theory |

| Research process | focused; deals with known variables; uses established guidelines; static designs; context free; objective | holistic approach; unknown variables; flexible guidelines; ‘emergent’ design; context bound; subjective |

| Form of reasoning | deductive—from general case (theory) to specific situations | inductive—from specific situation to general case |

| Nature of findings | numerical data; statistics; formal and ‘scientific’ | narrative description; words and quotes; personal voice |

| Researcher beliefs | there is at least some objective reality that can be measured | there are multiple, constructed realities that defy easy measurement or categorization |

| Research literature | relatively large | relatively limited |

| Research question | confirmatory or predictive | exploratory or interpretive |

| Research skills | statistics and deductive reasoning, and able to write in a technical and scientific style | inductive reasoning, attentiveness to detail, and able to write in a more literary, narrative style |

Process

Interactive approach

The interactive model of qualitative research proposed by Maxwell (2012) consists of five components, each of which addresses a different set of questions essential to the consistency of a study:

Goals

- Why is your study meaningful?

- What questions do you want it to address, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence?

- Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should we care about the results?

Conceptual framework

- What do you think is going on with the topics, issues, or people you want to study?

- What theories, beliefs, and prior research are you basing your study on, and what literature, prior studies, and personal experiences will you draw on to understand the people or issues you are studying?

Research questions

- What exactly do you want to learn or understand through this study?

- What do you not know about the things you are studying and what do you want to learn?

- What questions do you want your study to answer, and how are these questions related?

Methods

- What will you do in conducting this study?

- What approaches and techniques will you use to collect and analyze your data, and how do they represent an integrated strategy?

Validity

- To what extent might your results and conclusions be wrong?

- What plausible alternative interpretations and validity threats exist, and how will you deal with them? How might the data you have or might collect support or challenge your ideas about what is going on?

- Why should we believe your findings?

Goals

The emerging nature of qualitative research requires clear goals (Maxwell, 2012).

A clear understanding of the goals motivating your work will help you avoid losing your way or spending time and effort doing things that don’t advance these goals.

- Goals justify and guide the study

- Goals shape the methods, and conversely the methods that are feasible in your study will constrain the goals

- Goals shape the descriptions, interpretations, and theories

Three types of goals:

- Personal: goals that motivate you to do this study; they can include a desire to change some existing situation, a curiosity about a specific phenomenon or event, or simply the need to advance your career.

- Practical: goals that are focused on accomplishing something—meeting some need, changing some situation, or achieving some goal (e.g., generating results and theories that are understandable and experientially credible, both to the people being studied and to others).

- Intellectual: goals that are focused on understanding something, gaining some insight into what is going on and why this is happening.

There are five particular intellectual goals for which qualitative studies are especially useful:

- Understanding the meaning of events, situations, experiences and actions.

- Understanding the context in which the participants act and the influence this context has on their actions.

- Identifying unanticipated phenomena and influences.

- Understanding the processes by which events and actions take place.

- Developing causal explanations.

These goals require an inductive, open-ended strategy.

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework is a tentative theory of what is happening and why.

A conceptual framework “explains, either graphically or in narrative form, the main things to be studied—the key factors, concepts, or variables—and the presumed relationships among them.” Miles & Huberman (1994, p. 18)

The conceptual framework of your study is the system of concepts, assumptions, expectations, beliefs, and theories that supports and informs your research (Maxwell, 2012). It is constructed, not found.

- A useful theory gives you a framework for making sense of what you see (enables you to classify data and reveal relationship to other data; draws your attention to events or phenomena; sheds light on otherwise ignored relationships).

- However, No theory will accommodate all data equally well (some data may be ignored) and can illuminate everything.

- To address this limitations, multiple perspectives should be considered.

Research questions

In addition to the generic guidelines on the function and design of research questions outlined in the process chapter, Maxwell (2012) points to two specific issues that you should keep in mind in formulating research questions for qualitative research:

- Include the context: In qualitative research it is often more appropriate to formulate research questions in particular terms. For instance, you should ask “How do musicians adapt their professional role identity in response to gnerative AI systems?” in contrast to “How do employees adapt their professional role identity in response to these AI systems?”

- Focus on process: The real strength of a qualitative approach is in understanding the process by which phenomena take place not determining wether a particular result is causally related to one or antother variable and to what extend these are related. Process questions focus on how and why things happen, rather than whether there is a particular difference or relationship or how much it is explained by other variables.

Methods

Lay out a tentative plan for some aspects of your study in considerable detail, but leave open the possibility of substantially revising this if necessary. Maxwell (2012, p. 234)

Maxwell (2012) emphasizes the importance of finding a balance between having a clear structure for the research design while also allowing for flexibility to adapt to emergent insights and unexpected developments during the study.

- Sampling: Consider purposive and theoretically informed sampling strategies. Choose participants, cases, or settings that are relevant to your research questions and can provide valuable insights.

- Data collection strategies: Select appropriate data collection methods that align with your research questions and objectives. These methods could include interviews, observations, document analysis, and more.

- Triangulation: Incorporate triangulation by using multiple data sources, methods, or analysts to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings.

- Data Analysis: Employ systematic and iterative data analysis methods. Maxwell suggests using techniques like thematic analysis, content analysis, and constant comparison to identify patterns, themes, and relationships within the data.

Validity

Validity in qualitative research may differ from that in quantitative research, it remains a crucial consideration for ensuring the quality and rigor of the study.

Some key points Maxwell (2012) makes about the validity of qualitative research:

- Triangulation: involves using multiple sources of data, methods, or perspectives to cross-validate findings. By combining different data sources or methods, researchers can strengthen the validity of their interpretations.

- Chain of evidence: involves documenting the steps taken throughout the research process to establish the dependability and confirmability of the study findings.

- Thick description: providing rich and detailed descriptions of the research context, participants, and findings can enhance the study’s validity by allowing readers to assess the transferability of the findings to other contexts.

- Negative case analysis: actively seeking out cases or instances that do not conform to emerging patterns or themes can help avoid confirmation bias and enhance the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

- Member checking: involves sharing your interpretations with participants to validate the accuracy of your findings. This process helps ensure that participants’ perspectives are accurately represented.

- Peer involvement: seeking input from colleagues or other researchers who are not directly involved in the study can provide an external perspective and contribute to the validity of the study (e.g., use interrater-reliability).

- Reflexivity: reflecting on your own role as a researcher, biases, and potential influences on the study can enhance the validity of the interpretations.

Data collection

Overview

Choose data collection methods that are appropriate for addressing your research questions and objectives. Consider whether methods such as interviews, observations, focus groups, or document analysis are best suited to capture the data you need.

- In-depth interviews for exploring participants’ perspectives, experiences, and meanings. These interviews allow for open-ended discussions and probing for deeper insights.

- Observations in which behaviors, interactions, and situations are directly observed and recorded. In participants observations, the researcher commits intensive, long-term involvement and becomes part of the context under study.

- Focus groups involve group discussions around a specific topic or theme. They can provide insights into group dynamics, shared experiences, and social interactions.

- Document analysis can offer valuable insights into cultural, historical, or organizational contexts. Documents can include written texts, images, videos, artefacts and archival materials.

Use multiple data sources, methods, or perspectives to enhance the credibility and validity of the study. Triangulation involves cross-validating findings by comparing information from different sources.

Sampling

Purposeful or theoretical sampling involves selecting participants, cases, or settings based on their relevance to the research questions and the study’s theoretical framework (Maxwell, 2012).

Purposeful sampling can be used to …

- achieve representativeness or typicality of the selected attitudes, individuals, or activities. Avoid significant random or chance variation in your sample.

- adequately capture heterogeneity in the population. Ensure that the sample not just represents the typical members or a subset of the entire range of variation.

- examine of cases that are critical to the theories from which the study started or that were later developed. Select participants or cases that meet specific criteria relevant to the research questions.

- make specific comparisons to illuminate reasons for differences between settings or individuals, a common strategy in multi-case qualitative studies. Selecting participants who constitute or reflect those differences.

Interviews

Most commonly interviews are of a semi-structured nature, guided by an interview guideline (containing topics and questions) and following a conversational form (follow-up questions, targeting emerging topics).

Some recommendations:

- Interviews should be recorded and transcribed. Use memory logs for casual interviews.

- Show enthusiasm and be attentive to participants’ needs

- Clarify any confusion or concerns during the interview

- Evaluate the quality of responses (e.g., supplement interviews with observations)

Data recording

Recording data accurately and systematically is a critical aspect of qualitative research. Proper data recording ensures that the information collected during data collection remains organized, accessible, and ready for analysis (Maxwell, 2012).

Common options include audio recordings, written notes, field journals, photographs, and video recordings.

Here are some guidelines for how data should be recorded in qualitative research:

- If you’re conducting interviews or discussions, transcribe audio recordings into written text to allow for detailed analysis and coding of participants’ responses.

- Take thorough and detailed notes during observations, interviews, and interactions. Note down participants’ behaviors, quotes, non-verbal cues, and any contextual information that might be relevant to the study.

- Create structured templates or forms to guide note-taking. This can help ensure that you capture specific aspects consistently across different data collection sessions.

- Maintain a field journal to record your reflections, thoughts, and observations as a researcher. Document your own emotions, biases, and insights that arise during the data collection process.

- Include timestamps in your notes to track when specific events, comments, or interactions occurred. This is especially important for understanding the sequence of events.

- Document the context in which data is collected. Include information about the setting, participants, your role as a researcher, and any relevant external factors.

- Review your notes or recordings after data collection to ensure accuracy. Clarify any unclear points or discrepancies.

- Keep a record of your own reflections on the data collection process, challenges faced, and any deviations from the original plan. This transparency adds to the trustworthiness of the study.

Transcription

Transcribing interview data can be a very time consuming job. If you want to speed things up without using (free) SaaS-offerings, you might test aTrain.

aTrain is a tool for automatically transcribing speech recordings utilizing state-of-the-art machine learning models without uploading any data. It was developed by researchers at the Business Analytics and Data Science-Center at the University of Graz and tested by researchers from the Know-Center Graz.

Key Features:

- Completely offline transcription on your computer

- Nvidia GPU usable (CUDA required) for faster than real-time transcription

- Microsoft Store installation

- Speaker detection

- Limited to one language fort he whole interview

- Can translate audio to english (Choose language EN in the settings)

Data analysis

Interactive model

Miles & Huberman (1994) proposed an interactive model for qualitative data analysis that involves a cyclical process of data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing. This model is widely used in qualitative research to manage and make sense of large amounts of qualitative data. The model emphasizes an iterative approach where researchers move back and forth between different stages to refine their understanding and develop insights. Here are the key components of the model:

- Data collection: The process begins with collecting qualitative data, such as interviews, observations, or documents. This data can be in the form of transcripts, field notes, or any other recorded material.

- Data reduction: In this stage, researchers start the process of data analysis by reducing the volume of raw data into meaningful and manageable units. This involves coding, categorizing, and organizing the data to identify themes, patterns, and relationships.

- Data display: After data reduction, researchers create visual representations of the data, such as matrices, charts, diagrams, or summaries. Data display helps researchers see the patterns and connections more clearly and facilitates comparison and interpretation.

- Conclusion drawing/verification: This stage involves drawing conclusions from the analyzed data. Researchers interpret the patterns and themes identified and develop insights, explanations, or theories. The conclusions drawn should be supported by the data and aligned with the research objectives.

The process is iterative, meaning that researchers continuously move back and forth between the different stages. As new insights emerge, researchers might return to data reduction, refine data displays, or modify conclusions.

Techniques for drawing and verifying conclusions:

- Verification strategies that enhance the credibility of the findings. These strategies include member checking (feedback from participants), peer debriefing (input from colleagues), and triangulation (using multiple data sources or methods).

- Pattern matching: a technique used to compare the emerging findings with existing theories, literature, or conceptual frameworks. Researchers assess how well the observed patterns align with or deviate from established concepts.

- Comparison: Researchers compare data across different cases, contexts, or groups to identify similarities, differences, and variations. This helps in developing a nuanced understanding of the phenomena under investigation.

- Reflexivity: Throughout the process, researchers engage in reflexivity by critically reflecting on their own assumptions, biases, and perspectives that might influence the analysis. This self-awareness contributes to the rigor of the study.

Coding

Coding is a fundamental process in qualitative data analysis that involves systematically assigning labels or codes to segments of data, such as text, images, audio, or video, in order to categorize and organize the data based on specific themes, patterns, or concepts. Coding allows researchers to transform raw data into a more manageable and structured form, facilitating the identification of meaningful insights and patterns within the data.

There are two main types of coding in qualitative research:

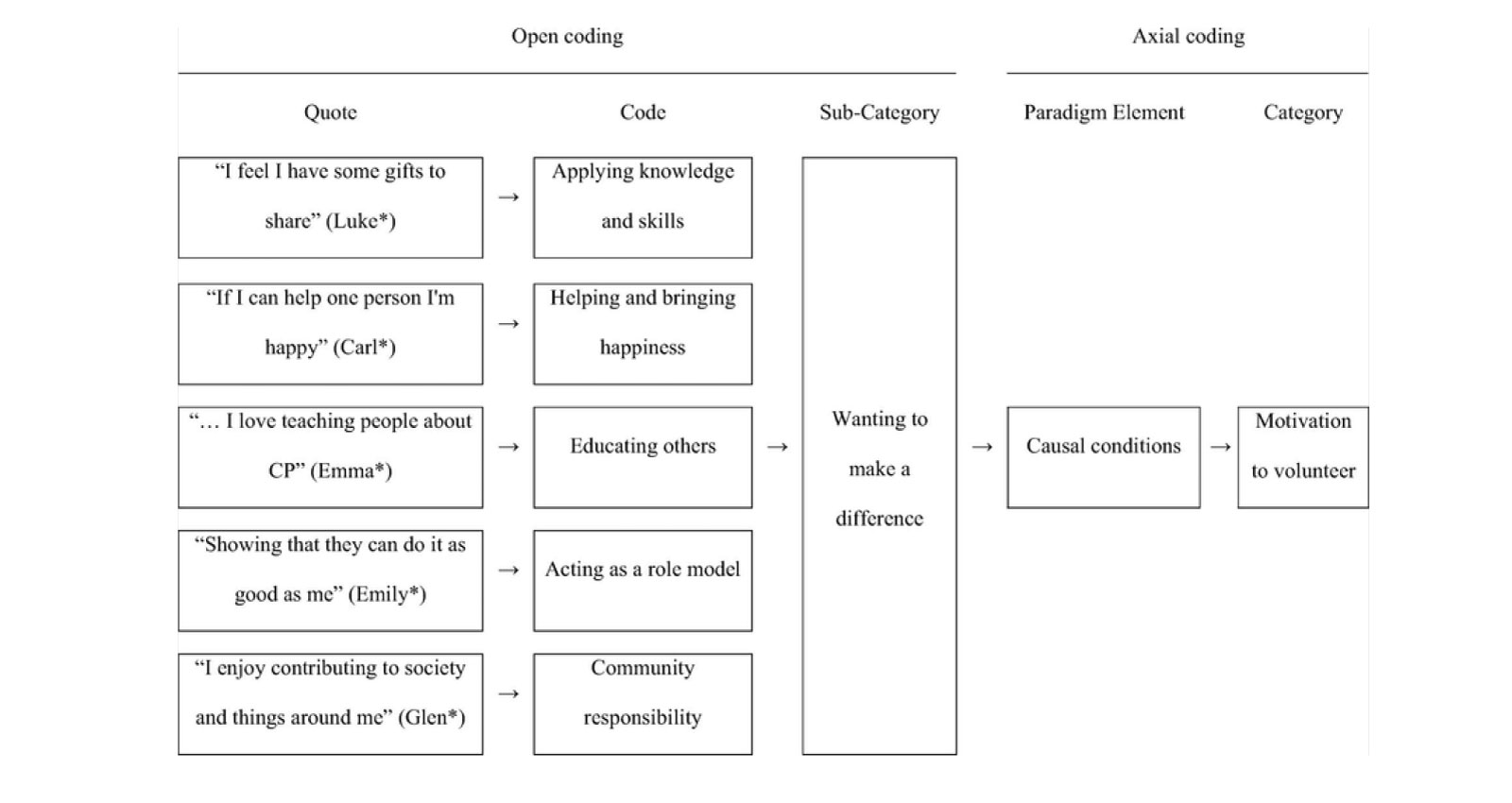

- Open coding involves breaking down the data into smaller units and assigning initial codes to capture the most basic concepts, ideas, or incidents present in the data. It is a process of exploring and identifying potential themes without preconceived notions, allowing for the emergence of new insights.

- Axial coding involves analyzing the initial codes (result of open coding) and their relationships to identify broader themes and concepts. Researchers examine how codes relate to each other and form more abstract categories. This process involves connecting subcategories and exploring the relationships between them.

- Selective coding: This stage involves further refining and selecting the most relevant and central categories that capture the essence of the data. Researchers focus on integrating and refining the categories to create a coherent and meaningful framework that represents the main themes and patterns in the data.

The coding process can be done manually or using specialized software designed for qualitative data analysis. During coding, researchers often create a coding scheme or codebook that outlines the definitions and descriptions of each code. This ensures consistency and reliability in coding, especially when multiple researchers are involved.

Example

Additional techniques

- Memoring: subjective commentary or reflection about what was happening at the time or place of the data collection, usually noted in a case/research diary

- Content analysis: semantic analysis to uncover the presence of dominant concepts in conceptual content analysis, text material is examined for the presence, frequency and centrality in relational content analysis, the co-occurrence of concepts is analyzed

- Critical incidents: identification and examination of ‘events’ or ‘states’ and the transition in between (i.e., reveal temporal or logical relations)

- Discourse analysis: analysis of the structure and unfolding of a communication (e.g., analysis of the use or evolution of phases, terms, metaphors, etc.)

Specific approaches

Case study

Case studies are the most popular form of qualitative methods in IS (Yin, 2009).

Following key points capture the essence of what makes case studies a valuable qualitative research method:

- Contextual understanding: Case studies investigate phenomena within their real-life context and provide deep insights into complex interactions

- In-depth analysis: Case studies involve thorough examination of cases, using qualitative data sources like interviews and observations.

- Exploration of “How” and “Why”: Case studies focus on understanding causal relationships, mechanisms, and processes.

Single case study

Single case studies are often used to gain a deep understanding of a specific case, exploring its unique characteristics, contexts, and processes (Yin, 2009).

- The focus is on providing an exhaustive and comprehensive analysis of a single case, exploring the complexity and intricacies of that particular phenomenon.

- Single case studies can contribute to theory generation by providing insights into patterns, mechanisms, and relationships within the single case.

- They are particularly suitable for exploring novel or less-studied phenomena, where little existing knowledge is available.

- Single case studies excel at providing rich contextual understanding, emphasizing the interplay of various factors within a specific setting.

- The transferability of findings to other contexts might be limited due to the focus on a single case.

Multiple case study

The primary goal is to draw comparisons and contrasts among cases, seeking to understand broader trends, commonalities, and variations (Yin, 2009).

- Multiple case studies emphasize the comparison of cases to identify common patterns, variations, and themes across cases.

- Multiple case studies are often used to test or refine theories, as findings across multiple cases can provide stronger support for generalizable insights.

- Researchers intentionally select cases that vary in relevant dimensions, allowing for the exploration of how different contexts influence the phenomenon.

- Findings from multiple case studies might be more transferable to similar contexts due to the diversity of cases examined.

Action research

Action research is a dynamic and participatory approach that focuses on practical problem-solving through iterative cycles of planning, action, observation, and reflection. It empowers participants, generates contextually relevant solutions, and aims to bring about positive changes in real-world situations.

- Action research involves researchers working closely with participants to address real-world problems.

- It focuses on identifying and addressing specific problems, challenges, or issues faced by individuals, groups, or organizations.

- Action research involves a cyclical process of planning, action, observation, and reflection. Each cycle informs the next, leading to continuous improvement.

- It aims to produce practical solutions and interventions that lead to positive changes in the researched context.

Action research cycle

Grounded theory

Grounded theory relies on inductive generation of theory that is grounded in qualitative data about a phenomenon that has been systematically collected and analyzed (Glaser & Strauss, 2017).

Urquhart et al. (2010) identified four main characteristics of grounded theory:

- The main purpose of the grounded theory method is theory-building, not testing.

- Prior domain knowledge should not lead to pre-conceived hypotheses or conjectures that the research then seeks to falsify or verify.

- The research process involves the constant endeavor to collect and compare data and to contrast new data with any emerging concepts and constructs of the theory being built (i.e., iterative theory-building).

- All kinds of data are applicable and are selected through theoretical sampling.