Learning objectives

After completing this unit, you will be able to:

- Distinguish leadership from management and explain why the digital age demands distinct leadership capabilities.

- Explain what mental models are and why a latticework of models improves decision-making under complexity.

- Apply core generic, systems thinking, and human behavior mental models to leadership scenarios.

- Evaluate the limitations of any single mental model using the “map vs. territory” principle.

Introduction

Digital leaders empower people with vision, understanding, clarity and agility. Waltraud Glaeser, Leadership Coach

Everyday leadership — We have made leadership about changing the world, and there is no world in the world that does not begin with changing yourself. Drew Dudley

This course explores what it takes to lead in the digital age. Rather than treating leadership as a single skill or trait, we will build a diverse toolkit of mental models —a latticework— that helps you navigate the complexity, ambiguity, and rapid change that define modern organizations.

Definitions

Leadership

Winston & Patterson (2006, p. 8) define leadership as:

One or more people who selects, equips, trains, and influences one or more follower(s) who have diverse gifts, abilities, and skills and focuses the follower(s) to the organization’s mission and objectives causing the follower(s) to willingly and enthusiastically expend spiritual, emotional, and physical energy in a concerted coordinated effort to achieve the organizational mission and objectives.

This integrative definition by Winston & Patterson (2006) captures several key aspects:

- leadership is a relational process (it requires followers),

- it is purposeful (directed toward organizational objectives),

- and it is voluntary (followers expend energy willingly).

- We will return to this definition repeatedly throughout the course as we unpack what each component demands of leaders.

Management

Kotter (2017) differentiates leadership from management as follows:

Management is about coping with complexity,

while leadership is about coping with change

Management brings order and predictability to a situation. But that’s no longer enough—to succeed, companies must be able to adapt to change. Leadership then, is about learning how to cope with rapid change (Kotter, 2017).

- Management involves planning and budgeting.

Leadership involves setting direction. - Management involves organizing and staffing.

Leadership involves aligning people. - Management provides control and solves problems.

Leadership involves providing motivation.

Context of leadership

The digital age is coined by digital technologies (e.g., Social media, Mobile computing, Analytics/big data, Cloud computing — SMAC) that are inherently disruptive and that cause major changes (Karimi & Walter, 2015).

Verhoef et al. (2021) identifies three phases of these disruptive changes:

digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation.

- Digitization is the “the process of converting analog signals into a digital form, and ultimately into binary digits (bits)” (Tilson et al., 2010, p. 749).

- Digitalization is “a sociotechnical process of applying digitizing techniques to broader social and institutional contexts” (Tilson et al., 2010, p. 749).

- Digital transformation is “a process that aims to improve an entity by triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies” (Vial, 2019, p. 118).

Digital leadership

Digital technology has changed and is changing organizations’ structure, work environment, processes and culture, in an irreversible way, creating new challenges that leaders have to face.

Organizational leaders must work to ensure that their organization is capable of responding to the disruptions associated with the use of digital technologies and of responding to the changes (Vial, 2019), e.g., by

- dissolving inertia and resistance to change,

- leading employees to assume roles that were traditionally outside of their functions,

- acting as boundary spanners that foster close collaboration between business and IT functions,

- depending on analytical skills to solve increasingly complex business problems,

- ensuring that digital technologies are properly leveraged (i.e., used).

Digital leaders empower people with VUCA — vision, understanding, clarity and agility.

Mental models

We have established that the digital age creates unprecedented complexity and that leaders need vision, understanding, clarity, and agility to navigate it. But how do you develop these capabilities? The answer lies in how you think —specifically, in the quality and diversity of the mental models you bring to every situation.

The decision-making crisis

In today’s world we need to deal with an unprecedented scale of information. 2.5 quintillion bytes daily means our intuitive approaches to processing information are inadequate. Digital leaders need to cope with VUCA as the “new normal”, which is not a temporary state but the permanent condition of modern leadership.

According to Parrish (2020) information overload, system complexity, and VUCA environments cause significant decision-making challenges in several ways:

- When faced with overwhelming information and complexity, we tend to filter based on our existing biases, potentially missing critical variables that would lead to better decisions (i.e., multiplied blind spots).

- When information exceeds our processing capacity, we tend to rely on simplistic heuristics or familiar models even when they don’t fit the situation rather than the thoughtful application of diverse mental models.

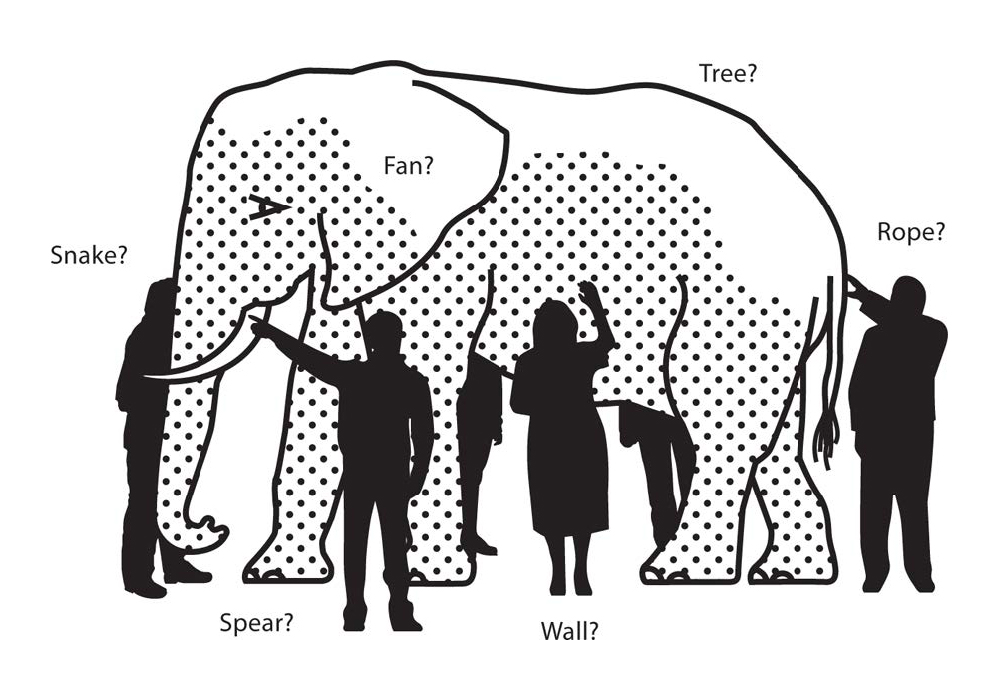

- The parable of the blind men and the elephant becomes even more relevant as in complex systems, each specialist sees only their part of the problem, but no one sees the whole picture.

- In complex systems, the consequences of decisions may be distant in time and space, making it harder to “keep our feet on the ground” and learn from experience (i.e, feedback delay).

- VUCA environments make it particularly difficult to anticipate the “second-, third-, and higher-order consequences of various choices”, which are crucial for decision-making.

The problem with specialization

Just as the blind men each touch a different part of the elephant—perceiving it as a wall, a rope, a fan, a tree, or a spear based on their limited contact—we tend to interpret complex problems solely through our specialized expertise. Whether economists, engineers, physicists, mathematicians, biologists, or chemists, we grasp partial truths about reality while missing the complete picture that would be visible if we combined our perspectives (Parrish, 2020, p. 21).

- Domain expertise creates tunnel vision

- Overuse of familiar tools (“to a hammer, everything looks like a nail”)

- Disciplinary silos limit innovation

Technical expertise alone is insufficient for effective digital leadership. This is why we need mental models from multiple disciplines - they help us see beyond our specialization.

Tetlock & Gardner (2015) emphasize that better decision-making comes not from specialized knowledge alone but from cultivating systematic thought processes that more accurately represent reality. For instance, their expert political judgment studies show specialists make worse predictions than generalists.

This further highlights how developing better mental models isn’t just philosophical—it produces measurably superior outcomes when facing uncertainty.

Latticework thinking

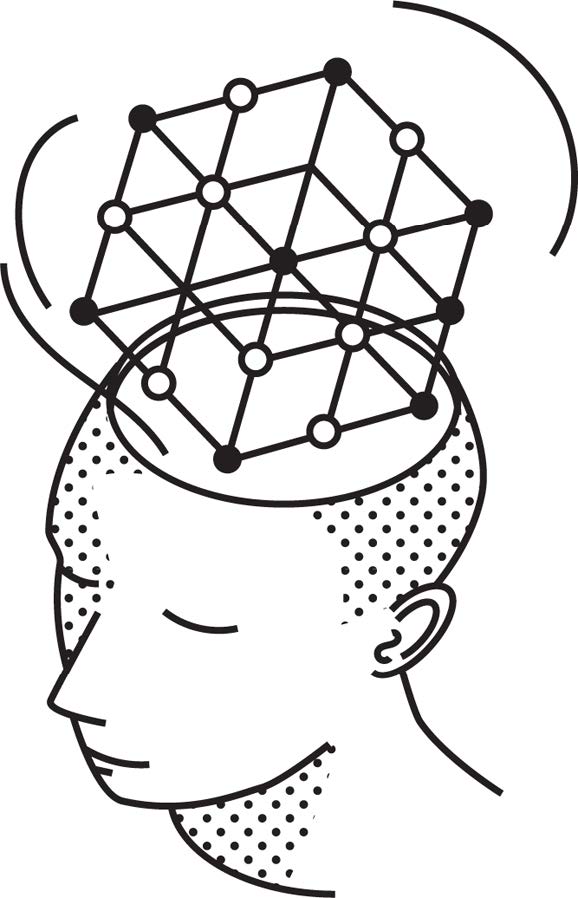

Mental models

Johnson-Laird (1983) shows that humans don’t naturally think using the rules of formal logic (like syllogisms or propositional calculus). Instead, we construct simplified mental representations or “models” of situations and mentally simulate what might happen within those scenarios.

A mental model is a cognitive representation such as a conceptual framework or worldview that helps us understand and interpret the world (Jones et al., 2011).

They function as

- filter for relevant information,

- framework for interpretation (e.g., cause-and-effect dynamics), and

- guide for decision-making.

Mental models can change over time through learning.

The latticework approach

Worldly wisdom requires models from all important disciplines (Parrish, 2020).

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models. Charlie Munger, Partner at Berkshire Hathaway (1924-2023)

(Parrish, 2020, p. 22)

When findings from different disciplines support the same conclusion, it strengthens the validity of that conclusion. And combining insights across fields can reveal patterns and principles invisible within any single discipline (remember the tale of the elephant).

Example: Netflix uses game theory principles to structure their recommendation algorithms, these create incentive structures for continued engagement, these incentives are implemented through specific UX design patterns, these designs leverage behavioral economics principles like hyperbolic discounting (valuing immediate rewards over future ones)

Mental models x leaders

Introduction

Mental models provide the understanding of how a system works and allow us to use heuristics to quickly navigate within that system.

Mental models are the key to making heuristics fast, frugal and accurate strategies. Such simple mental shortcuts in turn, enable rather than restrict decision-making under uncertainty (Gigerenzer et al., 2022).

Generic mental models

Generic mental models are models that are broadly applicable across multiple domains, disciplines, and situations, rather than being specific to a single field or context.

- First principles

- Elon Musk attributes Tesla and SpaceX’s innovations to breaking problems down to fundamental truths rather than reasoning by analogy — this is how they reimagined electric vehicles and rocket economics.

- Second-order thinking

- Most people stop at first-order consequences, but digital leaders need to ask ‘And then what?’ repeatedly.

- Probabilistic reasoning

- In environments of uncertainty, thinking in probabilities rather than certainties helps avoid both overconfidence and paralysis.

- Inversion

- Instead of asking ‘How can we make this project succeed?’ also ask ‘What would guarantee this project’s failure?’ - then avoid those conditions.

- Occam’s razor

- When presented with competing explanations or solutions, start with the simplest one with fewest assumptions.

Systems thinking models

Systems thinking models are mental frameworks that help us understand complex systems by focusing on relationships, interactions, and emergent properties rather than isolated components.

- Complex adaptive systems

- Digital ecosystems behave like biological ones — they organize themselves without central control or explicit coordination and, thus, can only be influenced but not controlled through well-chosen interventions.

- Feedback loops

- Systems are usually coined by reinforcing loops (where A increases B which further increases A) and balancing loops (where changes trigger countervailing forces) - understanding these dynamics helps predict how systems will evolve

- Emergence

- The most important properties of (digital) systems often are not designed but emerge from interactions — like how simple features of social networks created entirely new social behaviors (e.g., the hashtag effect).

- Network effects

- Understanding Metcalfe’s Law —that the value of a network grows with the square of the number of users— explains why platforms like LinkedIn or Slack become increasingly valuable and difficult to displace.

Human behavior models

Human behavior models are conceptual frameworks that help explain, predict, and influence how people think, decide, and act. These models are particularly valuable for digital leaders who need to understand both individual psychology and group dynamics when designing systems, implementing change, or leading organizations.

- Incentives

- These models explain how rewards and punishments shape behavior such as the principal-agent problem, intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation and hyperbolic discounting (i.e., the tendency to overvalue immediate rewards compared to future ones).

- Cognitive bias

- These models explain systematic errors in thinking and decision-making such as confirmation bias, framing effects, and availability heuristic (i.e., judging probability based on how easily examples come to mind).

- Social and group behavior models

- These models explain how people interact and organize such as status games (competition for position and recognition), reciprocity, and social proof.

Implications

Map vs. territory

The map is not the territory … the only usefulness of a map depends on similarity of structure between the empirical world and the map.1 (Korzybski, 1958).

As all models are wrong, but some are useful:

- Continually test and update models

- Maintain epistemic humility

- Seek disconfirming evidence

- Use multiple maps of the same territory

Build your latticework

Parrish (2020) recommends to begin with a handful of models from different disciplines rather than many from one field. Quality and diversity trump quantity. In the beginning, focus on mental models with the broadest application - like feedback loops, incentive structures, inversion, and first principles thinking. Read widely, but with purpose. Look for concepts that explain phenomena across multiple domains.

Put an emphasis on application as the key difference between collecting mental models and building a latticework is application. Use the models learned actively in your decision-making and keep a decision journal where you explicitly note which mental models you applied and review outcomes to refine your understanding.

Approach this as a career-long project — the compound interest of mental models accumulates over decades.

Three-step approach:

- Learn (study diverse fields)

- Apply (use models in real decisions)

- Reflect (record outcomes and refine)

Latticework x this course

Building your latticework — unit by unit

Throughout this course, each unit adds new mental models to your latticework. By the end, you will have built your own leadership latticework — a diverse, interconnected set of thinking tools you can apply to real leadership challenges.

The latticework grows with every unit:

- Unit 1 — First principles, inversion, second-order thinking, systems thinking, map vs. territory

- Units 2–8 — Each unit introduces domain-specific models (traits, paradoxes, motivation, teams, power, stakeholders, culture)

- Unit 9 — Storytelling as the meta-model for communicating your latticework to others

Your latticework canvas

Use this template to track your growing latticework throughout the course:

Keep this canvas as a living document. After each unit, note which mental models were introduced and — more importantly — reflect on how you might apply them. The compound interest of mental models accumulates over time: the more you practice connecting models across domains, the richer your leadership thinking becomes.

Remember Parrish’s three-step approach: Learn (study diverse fields), Apply (use models in real decisions), Reflect (record outcomes and refine).

Literature

Footnotes

Korzybski developed this concept during a period when many fields were grappling with the limits of human understanding - similar to our current AI era.↩︎